Every once in a while the question, “Who is an expat?” comes up in my foreigner abroad groups. Often enough at one point that moderators would shut down such posts. It may seem pedantic to ask. But the question of who is an expat, a migrant, an immigrant, or a foreigner is more relevant than ever between Brexit, Trump, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, and anti-immigration sentiment bolstering the growth of right-wing extremism throughout the world.

According to the dictionary expatriate is a verb, noun, and an adjective. Merriam Webster lists the first definition as banish, exile. The second involves withdrawing from, leaving, or renouncing allegiance to one’s native country. In the last it is a person who lives in a foreign country or the act thereof. On the other hand the Oxford dictionary consigns the definitions of exile or to be expelled to the realm of the archaic. For the English an expatriate is a person who lives outside their native country or the act of sending a person or money abroad.

Mawuna Remarque Koutonin writing in the Guardian proclaims that “expat is a term reserved exclusively for western white people going to work abroad.” Over at Girl vs Globe they agree with Koutonin. Meanwhile, according to the Grammarist the term expatriate carries the implication that expats will, or at least wish to, one day return to our countries of origin. Whereas immigrants leave their homes to create a new and permanent one in another country. Finally, at The Wall Street Journal, they concluded that “It depends on social class, country of origin and economic status.”

The English word expatriate is derived from the eighteenth century French word expatrier, meaning banish. Or from medieval Latin expatriat meaning ‘gone out from one’s country.’ Either way it referred to one exiled. The rise of the British Empire brought about the rise of the use of the word as well as its change in designation. With Empire came diverse new forms of British identity, particularly in the colonial world.

When the British Empire was at its crest in the 19th century the colonies, India in particular, offered a breadth of opportunity. Mostly for younger sons of upper class families and driven young men of the middle classes. Eventually colonial British communities developed identities of their own influenced by local cultures and their own ambitions. But the rigid class constraints of the homeland still applied, elitism and pedigree determined one’s position, and home comforts were modeled on those enjoyed by the British aristocracy.

To the people being colonized, however, their oppressors all seemed one corrupt mass. By the time the word expatriate, or expat, achieved widespread modern use in the mid-20th century the stereotypical image of the white suited, pale faced expat sitting at the club bar sipping a gin and tonic in the tropics was firmly in place. To many, an expat is someone who arrives in a new country with no intention of understanding or connecting to its people or culture, who makes no effort to learn the language, or to integrate in any way into local society.

This view is bolstered by the fact that in the twentieth century until the 1990s, when the Internet gave rise to unprecedented access to mobility, an expat posting often involved a white collar professional being transferred to an international office by a company or a government for what would typically be a short term assignment of a few years. This was routinely accompanied by a lucrative package of generous benefits, the expat package, including high wages, housing, and schooling for children. The result is that the word expat has become a representative of white supremacy, racism, and classism.

Expats, immigrants, refugees, we are all migrants. For me the term expat had less to do with the color of a person’s skin than the color of their passport. People from wealthy countries doing often dangerous blue collar jobs may still be considered expats. There were also socioeconomic connotations. Regardless of where a person was from if they were doing white collar work in the foreign country they may be an expat. The people, migrants, that are called expats today have chosen living abroad as a lifestyle. Expats can be Asian, African, or from the Americas. We can be from anywhere and look like anyone.

The biggest differences between expats and other migrants is that expats are people who have left their home countries voluntarily, are working/studying temporarily in another country but plan to, eventually, return “home”. I have a number of former students now working in the States and other countries that I consider expats as they plan to go back to Korea. Someday. Refugees, whether fleeing violence, or environmental or economic devastation, are running away from something rather than toward it. There is nothing voluntary about their status. Immigrants, on the other hand, move to another country permanently. The new country is to be “home”, if not for them then their children and grandchildren.

As mentioned being an expat is partially defined by an absence of permanence. Be it months or years abroad an expat intends to return home. Or, at least, to leave the current country of residence. Nowadays it’s becoming common for expats to take a string of different assignments. I have run into people who have been abroad decades and lived in a dozen different countries. Which leads to the other big difference between being an expat vs an immigrant. Assimilation. Immigrants are expected to assimilate. Expats generally aren’t, and don’t. (Whether they should is another question.)

This is probably connected to the fact that true assimilation typically takes years, if not generations. Since expatriation is a temporary state it makes sense that expats don’t fully integrate into the culture. Indeed, doing so in three or four years, or less, is an almost impossible task. However, there is a huge difference between not assimilating and being an asshole. We are, essentially, long term visitors. As such we should treat our host countries with the same respect with which we would treat the home of anyone who has invited us in.

Expats follow the same patterns as all migrants. When people move to a new country, expat or immigrant, we tend to find more of our own. We form Chinatowns, Korea Towns, and Little Odessas. We hole up in foreigner friendly bars where we can speak our own languages (or English) and commiserate with each other on the difficulties of navigating the massive and continuous change we find ourselves confronted with daily, hourly, and minute by minute. This is hardly a surprise as community is one of the most basic of human needs.

The problem is the sense of entitlement that often comes from being middle class or higher, wealthy, white, and/or from a wealthy country. For example, “expats” married to locals and having been in country decades with no intention of returning to their home countries, yet have not only not bothered to learn the language, they constantly belittle everything and everyone around them. Then there are people like some in old British bases whose families have been in country for literal generations yet still they refer to themselves as expats and hold themselves apart. Worse are the people for whom nothing is ever as good as “back home” and who let everyone around them know it, loudly and often. Other examples abound.

This does not include everyone who is all of these things, much less any one. And in some cases it’s not the expat community that holds itself apart so much as it’s the local community that refuses to open up- as is their right. Korea, for example, can focus on purity of blood embracing “foreign born Koreans” who have never lived in the country over “foreigners” born and raised in Korea. Even if they have a Korean parent. Here in Denmark there is more acceptance of biethnic people with a Dane parent, but there seems to be a hard, if invisible, line between being a Dane versus being Danish. Even here things are not exactly welcoming to foreigners. And they are swinging further right with several new laws in place punishing Danish people for living abroad or having foreign spouses.

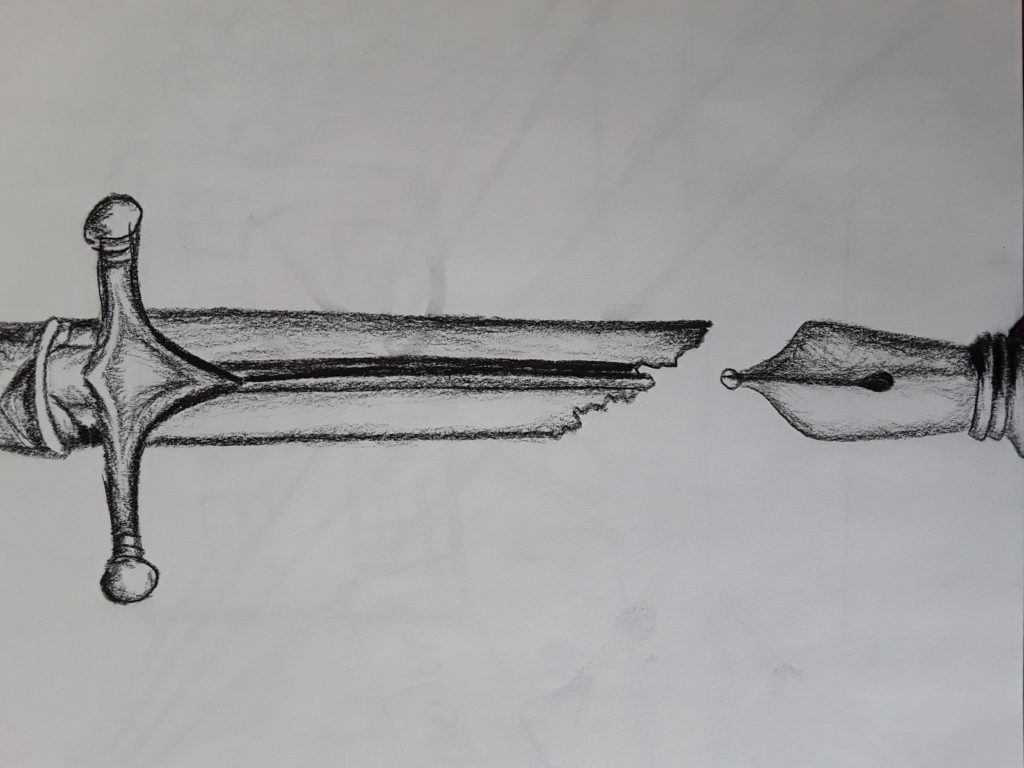

Which is why who gets to claim the title of expat is important. Language matters. The pen is, after all, mightier than the sword. Language is a political tool. It can be used to elevate or to dehumanise. Expat is a label used by people who feel a certain kind of way about themselves. I came into this article with preconceived notions that what defines an expat has to do with what we do, where we are from, or some combination thereof. But in writing this I have come to the conclusion that an expat is whoever cares to claim the label.

As migrants, be we expat, immigrant, refugee, we are all just trying to make our lives work in alien cultures that can be harsh, confusing, amazing, inspiring, sometimes all at once. We share the same longing for what once was, which is often the never will be again. We struggle with the fact that what was common sense back home isn’t in our new environments. We have amazing kids who don’t understand where we come from or the sacrifices we’ve made to allow them to be who they are, to have the experiences they have. We’re just people, trying to figure our shit out, like everybody else on the planet.

Other sources

http://www.bbc.com/capital/story/20170119-who-should-be-called-an-expat

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09585192.2016.1243567

https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/10/expat-immigrant/570967/

http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/mobile/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199297672.001.0001/acprof-9780199297672-chapter-1