Part of National Museums Liverpool (NML) the International Slavery Museum is free with donations, of course, accepted. It is on the third level of the Merseyside Maritime Museum which is located in the Albert Dock area of Liverpool. It is mere yards away from the dry docks where eighteenth century slave trading ships were repaired and fitted out. Walking past the other museums in the space does not prepare one for the International Slavery Museum.

Why Britain? Britain became a strong force for the abolition of slavery.* But not until after it reaped its own fortune in the trade. In the 18th century Britain was the leading slave-trading nation. Its cities were fundamental to a global system that enslaved at least 12 million African people. Besides the wealth generated directly from slavery there was that produced by the milling of slave grown cotton, the finance industry’s insuring of slave ships and their human cargo, and the gun industry – which needs no explanation.

Why have this museum in Liverpool? Liverpool alone was responsible for half the British slave trade, and her ships carried approximately 1.5 million enslaved Africans into slavery. By the 1780s Liverpool was considered the European capital of the transatlantic slave trade transforming Liverpool into one of Britain’s most important and wealthy cities of the time.

Born of NML’s Transatlantic Slavery Gallery, which originally opened in 1994, the International Slavery Museum opened on the 23rd of August in 2007: Annual Slavery Remembrance Day and the bicentenary of the abolition of the British slave trade. The museum is a campaigning museum. One of the main goals is to be an active supporter of social change and social justice. The display space is split into three galleries; Life in West Africa, Enslavement and the Middle Passage, and Legacy.

The museum itself is well put together with interactive touches, interesting and thought-provoking exhibits, does a thorough job of detailing the timeline of transatlantic slavery, and acknowledges the existence of modern slavery with art and narratives. It discusses, even challenges, the concept of freedom. The West African wing is a reminder that there was life, rich culture, and complex society long before the intrusion of European colonization and the ravages of the transatlantic slave trade.

One thing that I found of particular interest is the Sankofa project. Of the Akan language of Ghana, Sankofa teaches that we “must go back to our roots in order to move forward.” The aim of the project is to; through stories, photographs and objects, highlight the history of Black Liverpool. The museum offers communities and individuals resources for looking after the things that are important in telling the different sides of the story.

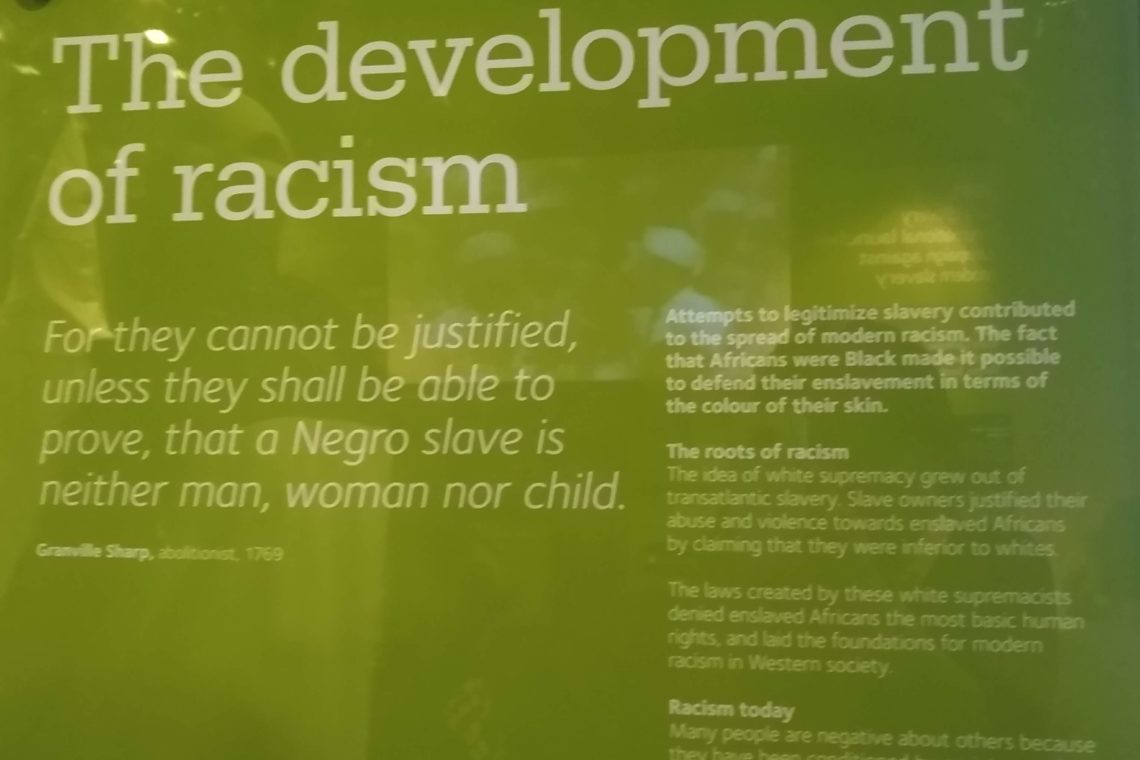

The museum attempts to balance the cruel realities of transatlantic slavery against a story of Black resistance, achievement, and humanity. The goal was to avoid linking Black and African history only with slavery or with the negative. They are successful but in doing this, they also avoid much in the way of explicit discussion of the slavers and slave profiteers. This creates a distance between the racism and discrimination born of the legacy of transatlantic slavery and those responsible for the acts of enslavement and colonization. This stands out strongly with the Windrush Scandal** blowing up just last year illustrating slavery’s continued impact on Britain. Particularly in the recent details of how that scandal has been handled.

As Kehinde Andrews over at the Guardian put it, “Slavery and colonialism embedded racism into the fabric of society. Our historical narratives are delusional precisely because they prevent us from dealing with our complicity in maintaining an unjust racial order. Racism is not in our minds; it is in the schools, prisons and on the streets.”

*In order to make abolition possible, slave owners were paid reparations to tune of twenty million Great British pounds. At the time this was 40% of the national budget of the Treasury. The loan the government took out was so large that it was not paid back in full until 2015. Meaning that, through taxes, the descendants of enslaved people actually paid reparations to the people who enslaved their ancestors.

**The Windrush scandal.

The Windrush generation refers to immigrants who were invited to the UK between 1948 and 1971. Named the Windrush generation after the British ship the Empire Windrush, which arrived with 492 passengers in 1948 the Windrush generation is made up of people of the British Commonwealth originally from the Caribbean. Black folks.

The 1971 Immigration Act gave Commonwealth citizens who were already living in the UK indefinite leave to remain. For this reason, and because many of the Windrush generation arrived as children on their parents’ passports and never realized they were not citizens, many never formally became British citizens. Instead, they have lived in Britain as legal residents paying into the system for decades.

However, under Theresa May’s “hostile environment policy” aimed at illegal immigration, immigration law changes in 2012 forced landlords, employers, and civil service offices to proactively prove that their tenants, employees, and service users had the proper legal status to be in the United Kingdom. People were forced to prove continuous residence in the UK since 1973, something that turned out to be almost impossible for many.

During the scandal legal residents who had lived their whole lives in Britain were denied essential services, lost their jobs, and some were even deported back to “home” countries in which they had not set foot in decades.

As a result, the government vowed that all Windrush generation immigrants would be granted citizenship papers with waived application fees. Those who suffered as a result of the policy change, it claimed, would also receive compensation. However, nearly a year on, a compensation scheme has yet to be launched. Meanwhile, many of those affected remain in dire financial circumstances due to losses caused by the government.